“After the final no there comes a yes”

“After the final no there comes a yes, and on that yes the future world depends.” — Wallace Stevens

Last week I wrote myself a letter and mailed it. I just got it back, and as I write this, have not yet opened it. Ok, I just opened it. What is the part of me, I wonder, that waits to open it until I am writing to you? I think it is the same part that reaches, in a myriad of ways, for the sustaining sense of otherness. But when I wrote the letter I was depending on the four-year-old me who says “write this letter as if it is from the kindest-wisest most encouraging person you know.”

“After the final no there comes a yes”

After the final no there comes a yes; And on that yes the future world depends.

— Wallace Stevens, Well-Dressed Man With a Beard

I am writing on the winter solstice, the darkest night. I have just awoke to the first snow and below freezing temperatures here in Kentucky. The bird feeder has been blown down with gusts of wind. The whole country is in this storm. It is time to plant seeds inside, to plant prayers for the coming light, for the new year.

It is time to do the thing you are afraid to do. It is time to do the thing I am afraid to do: send my book out to publishers. I am imagining that saying this aloud to you will give me courage.

Writing peels away layers, forms questions, what do I want for my readers? I see what is probably obvious, that all my writing turns toward what Robert Johnson called the numinous “slender threads” — fate, destiny, synchronicity, faith in what cannot be told, faith in the transforming ability to make a bridge between the visible and invisible world with your hands. Give your hands something to devote themselves to. Dream while you are awake. With this devotion and attention, work naturally becomes prayer. Every kind of mending is made possible.

Fishing the River

The land is like poetry: it is inexplicably coherent, it is transcendent in its meaning, and it has the power to elevate a consideration of human life.

— Barry Lopez

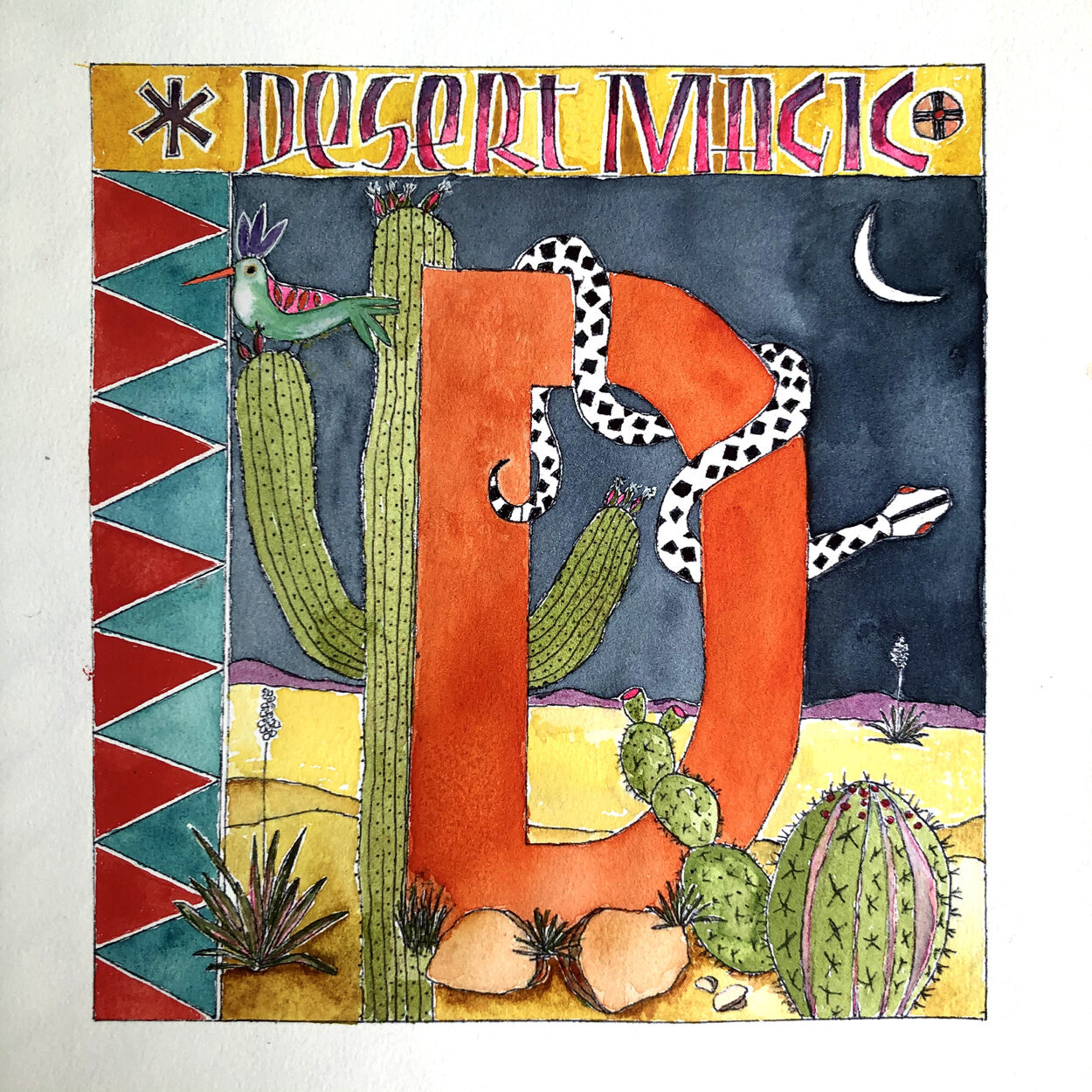

Anyone who has spent time in the desert, watching and listening, has felt the sense of depth and presence that defies the initial barren glance. I have taken many road trips to the New Mexico desert, and what follows is a true story of one I took years ago, headed toward Ghost Ranch.

Fishing the River

I am almost to the New Mexico border where the sign says, in big red letters, "You Are Leaving Colorado." Further down the road there's a second sign: “Welcome to New Mexico, The Land of Enchantment.” I have always wondered about that place between the two signs. It is some kind of demios oneiron, a village of dreams, that does not exist on any map.

Highway 17 is a rural mountain road circling above the Chama River. I have traveled it countless times on my way to teach at Ghost Ranch (named by the Spanish as a place of witches, “Ranchos de los Brujos”). This route is marked by reminders of our mortality. Rural New Mexican byways are decorated with descansos, a pastoral cross with flowers, honoring the resting place of one who has died on the road. Often I have stopped when seeing an old cemetery guarded by iron gates and filled with plastic roses and small figurines of the Virgin Mary. The gravestones have old writing and engravings of crosses, of which I have made many rubbings. New Mexican graveyards are distinct — flavored with Native American and Mexican roots. Mary is represented as the Virgin of Guadalupe, "a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars." There are many stories of The Virgin of Guadalupe, going back to the 1500’s. She symbolizes the bridge between heaven and earth.

To make a tax-deductible donation to the Mabel Dodge Luhan Retreat, click here.

Uprooter of Great Trees

I want to tell you a story — a very old story — that I heard from Laurens van der Post.* It speaks to the necessity of embracing paradox, and off the suffering caused by dualistic thinking: when things are either this or that; when you are either going to succeed or fail; when anything or anyone is either good or bad; when something is either right or wrong. Dualistic thinking renders us unable to deal with the difficulties and paradoxes that life inevitably brings. Spending most of my daylight hours painting, I notice that I need to hold the paradox of having structure alongside the need to be self-forgetting — the fool who jumps in.

I shared this story in a recent class in New Mexico. One of the students arrived at the last minute because of a family emergency. For the entire week she chose to remain silent in her grief, only saying: I cannot speak about it. And so she worked, allowing her hands to give shape to her grief.

Once upon a time, in a faraway place…..